- WHAT should students know and be able to do by the time they exit our public education system at Grade 12, prepared for both college and careers? (These are the standards)

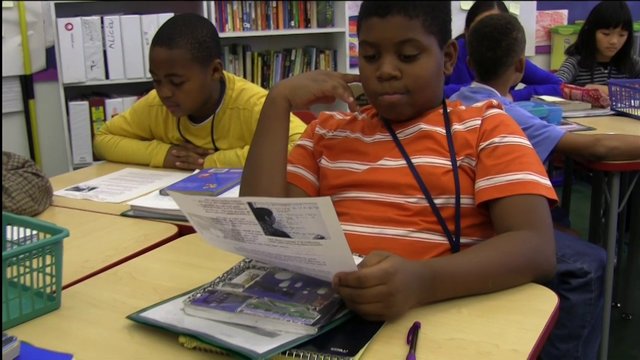

- HOW can we best teach them these things along the K-12 continuum in a way that is accessible for all students and cognitively sequenced for learning? (This involves the instructional materials and the instructional methods by which teachers enable learning.)

- WHY are these skills critical to students’ success beyond the K-12 system? (The target is to produce students that are both college and career ready.)

The Common Core State Standards are the WHAT. They are declarative statements and focus on skills that students should have at various grade levels. Take a 4th grader for instance: at 9 -10 years old, the standards identify that s/he should be able to: Determine the main idea of a text and explain how it is supported by key details; summarize the text. This is simply the WHAT. It does not imply how they are to learn that skill, or demonstrate mastery of that skill. Therefore, the methods by which a teacher organizes materials and sets up opportunities for a student to learn how to determine the main idea from a passage, then figure out key details that support this main idea and ultimately summarize the text is the HOW. This is where we see differentiation between teachers and the materials and methods they use to connect their students with concepts, topics, knowledge and skills.

[fusion_builder_container hundred_percent=”yes” overflow=”visible”][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”no” center_content=”no” min_height=”none”]

One teacher might follow his textbook’s structured activities around this skill. Students read about Westward Expansion using an excerpt from the book Desperate Passage that focuses on the plight of the Donner Party. The materials include a hand-out of the excerpt and students are directed to underline the main idea and circle key details that support the main idea, then write a one paragraph summary of the article in their own words prior to engaging an open discussion on the topic in class. During the discussion, the teacher connects this one event to larger themes they have been covering on the topic of Westward Expansion.

Another educator might opt to provide her students an online article (http://www.history.com/topics/donner-party) and read it aloud to them and have them notate in their own journals the main idea and write down at least 3 key details to support that idea. As a peer-to-peer exchange, the teacher places students into groups of 3 to compare their notes and come to a consensus on their 3 best collective details to report out to the rest of the class. For homework the students are given the article to take home and are asked to further review it and draw a flow-chart of decisions and circumstances that led to the Donner Party’s ordeal as a means of demonstrating their ability to summarize the event from the reading.

In both these instances, the key skills (the WHAT) being focused upon are Reading skills. More specifically, the reading of informational text as identified in the Common Core Standards for English Language Arts (http://www.corestandards.org/ELA-Literacy/RI/4). And in this specific case, the selected text is referencing a historical event, however it could be a piece of text describing the water cycle as a process (science) or how to save an image from a website for inclusion in a powerpoint presentation and cite it correctly (technical subject). The HOW provides teachers an opportunity to follow the guidelines of supporting instructional materials or to blend in their own unique methods in an attempt to make the activities more engaging, or differentiate the learning to accommodate for diverse learner needs, or provide students various means to demonstrate the intended skills.

The WHY of the exercise is a bit more complex. The WHY tries to establish the relative importance of the skill of Determining the main idea of a text and explaining how it is supported by key details; & summarizing the text. Well the short answer to parents and external stakeholders is…it is important because a cross-section of educators, business leaders, instructional specialists, cognitive development experts, and the like, referenced decades of research to determine its importance as an individual skill, and as a step within a continuum of reading skills that extend from grade K through grade 12. What we would hope, is that the importance of this skill and the others found in the CCSS are self-evident. They do represent a set of skills, that a large and diverse cross-section of communities both within and outside of education, collectively worked and agreed upon for the better part of 5 years. It is unprecedented in public education for this many segments of the education universe to agree on such a wide-ranging set of definitive skills for the topics of English Language Arts and Mathematics, and that, in and of itself, is not without its merits. However, it does not mean the standards are beyond reproach.

And I am not referring to conspirator fomented allegations that they represent some centrally-controlled attempt to consolidate children’s thinking and the operation of schools under the authority of the federal government. Anyone working on the standards knows all too well that the impetus and development of this framework began and persists at the state level and the powerpoints supporting this work lie far beyond the thinking and processes of the federal U.S.D.O.E.

No, when I open up the idea of dissension with the Common Core State Standards, I am directing educators and parents to consider evaluating the assertion that all of the skills are equally valuable for all communities and all learners at all grade levels. I’m challenged with the notion that the skills present in CCSS are so ground-breaking and unprecedented as to present a necessary departure from the existing curriculum, focus, and instructional support efforts of any given state or schools. The rhetoric surrounding the CCSS would have you believe that teachers need extensive professional retraining to understand and re-engineer their classrooms, assignments, and instruction to implement CCSS. This largely comes from those that provide said PD. Additionally, review and adoption of new and diverse instructional materials aligned to CCSS are purported to be of critical import for each and every district, as suggested largely by those in the business of selling said instructional materials.

However, consider the above Reading of Informational Text examples. As is the case with most of the CCSS, they can be addressed with existing or readily available materials with modifications made on how the materials are introduced and taught and how students are required to demonstrate competence. And the seemingly “big changes” in the end, as was the case in past standards-adoptions and reform movements, are that teachers and schools must embrace their right to their own analysis and focus on ordering and ranking standards as a means to make decisions on behalf of and with their communities to support the needs of their students.

The Common Core State Standards present the WHAT. Schools should inspect and analyze those for sure, with the needs of their families and students in mind and the culture of their communities at heart. But absolutely allow teachers to interpret and develop and share their own HOWS and make sure that many others are involved in coming to some conclusions on the WHYS in a way that makes best use of your existing talents, resources, experiences, and collaborative efforts.[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]

2 replies on “Common Core State Standards…The What. Not The How or The Why”

A clear analysis of purpose related to CCSS. But I disagree that only PD providers are promoting PD for CC implementation. I agree teachers don’t need new textbooks–at least in ELA; they can work with existing materials or gather new ones from the internet. Brian, I’m convinced you are a good teacher; you have various ideas of how to approach instruction. Sometimes, good teachers don’t realize that other teachers do not have the ideas to creatively approach instruction. That’s where PD comes in. The literacy standards are a reaction against past reading instruction that became a matter of following a prescribed process: predict, connect (usually self to text), and sometimes…summarize. Real reading is much more than anticipating what a text will be about or stopping to guess what may happen next. Moreover, real reading is about far more than considering how the text connects to one’s personal life or situation. To be successful in this world, one must learn to think beyond self: to research and weigh, to consider and mediate, to return to the text to evaluate and to research even more. Some teachers need PD to understand that learning is more than reading the chapter, answering questions at the end of the chapter only to start a new unit on Monday.

I agree with Dr. Dea Conrad-Curry that different teachers have different skills, and I do see Professional Development (perhaps not in the form it is currently rendered though) as a way to help some teachers refine and hone their craft. However, the intention of the post was to identify Common Core State Standards for what they are and are not. I have opted to openly question why the CCSS are being translated or rather exaggerated into massive PD and instructional materials implications. The best outcomes generated so far by CCSS are the consistent expectations applied to all schools to help all students achieve a certain level of skills independent of community or demographic. The challenge is re-modeling both PD and instructional materials access to ensure that expectation can be met.

And in the current world of PD, focusing on the expertise of the few to come in and remediate the limited creativity of the many is presumptuous and antiquated and hovers somewhere between Rhetoric and Ritual in practice. That is why I am inspired by models from both PARCC and SBAC as well as focused funding by the likes of the Hewlett and Gates Foundations to assemble large cohorts of teachers to review, consider, and discuss the standards and then devise and develop collective instructional approaches and materials to support classroom implementation. Success in this endeavor will not look like teachers being asked to assemble around professed PD experts, but will look like networks of collaboration where the cult of expertise lies in the day to day methods being used in thousands of classrooms, not the activities being conducted outside of the school day, away from the school site.

However I suspect that education, leaders and teachers alike, will be told and made to continue to believe that there is a conference somewhere, and a workshop somehow, that might just help them unlock critical understanding of these mysterious new CCSS and all of the instructional implications that come with them.